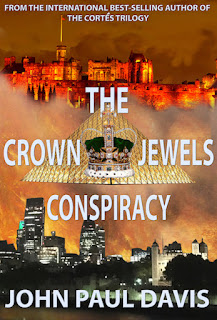

Interview with author John Paul Davis

Interview

1) The 1666 Fire of London features heavily in your thriller 'The Crown Jewels Conspiracy', when a contemporary gang of renegades attempt to reconstruct the fire in our century via launching a terrorist attack. Intrigued to read in your Afterword to the novel about the claims that the 1666 Fire was an act of deliberate arson. How seriously were they taken at the time? How seriously should the deliberate arson theory be taken now?

At the time, it was taken very seriously. Shortly after the fire, one Robert Hubert, a watchmaker from Rouen, actually admitted to having started it. Few historians, or even contemporaries, seem to have believed him. Though he was ultimately found guilty and executed, the trial was viewed as something of a sham. Of the seven signatories against him, three were from members of the Farriner family, who owned the infamous baker’s shop in Pudding Lane. Hubert’s testimony was inconsistent from the outset, despite his being able to accurately pinpoint the lost location of Farriner’s bakery. A search for his alleged accomplices, including one named Stephen Peidloe, proved unsuccessful and the captain of the ship Hubert had sailed on later confirmed he had not even been in England at the time.

Significantly, Hubert was not the only candidate. The fire had occurred at the height of the Second Anglo-Dutch War and only a short time following the burning of the Dutch coastal town of West-Terschelling under the leadership of the famed British Rear-Admiral Robert Holmes. As was typical in England, the event was celebrated with the lighting of bonfires and fireworks. In the aftermath of what was dubbed, ‘Holmes’s Bonfire’, a Wiltshire farmer alleged that a Dutchman took great offence at the celebrations. He also threatened the farmer that, ‘If you should live a week longer, you shall see London as sad a London as ever it was since the world began’.

Then, of course, there were accusations against England’s favourite foe – the French. According to the testimony of one Elizabeth Styles, a French servant had said to her the previous April that English maids will like Frenchmen better when there’s not a house left between Temple Bar and London Bridge – an event that would occur between June and October. The fire, of course, occurred 2-5 September.

To top this off, we have our prime candidate – a figure who was indirectly a significant influence on my novel, The Crown Jewels Conspiracy. A renowned maker of fireworks, the Frenchman Monsieur Belland – be very careful how your pronounce this one ;-) – was in the king’s employ at the time and is known to have been very angry when some pasteboard he ordered did not arrive on time. Belland is recorded as having stated that if it were not with him by the following week – the start of September – he would no longer need it. He is also reputed to have claimed that the fireworks included rockets that ‘fly up in a pure body of flame, higher than the top of St Paul’s, and waver in the air’ – something the fire is recorded as having achieved. Though the Frenchman was found innocent, the accusations are intriguing, to say the least, and, in my opinion, deserving of further research.

For those who are interested, I always enjoyed this National Geographic documentary on the Great Fire

2) The question of the Crown Jewels and what happened to them during the English Commonwealth appear in the above novel and 'The Cromwell Deception'. What is your view on the subject? Do you think that Cromwell did just leave them intact or started to melt them? The royal plate collection was melted down and I think that some paintings from the Royal Collection were sold off.

Sadly, I think many pieces were melted down. There is good evidence that the Diadem of St Edward was melted down; there is also evidence that the modern-day coronation crown, the crown of St Edward, was created from the same gold as its predecessor. Fortunately, parts of the original regalia have survived, including the coronation spoon, the ampulla, at least one of the swords and the Black Prince’s Ruby – this precious jewel sits within the Imperial State Crown. As you say, much was sold off to help the roundheads’ war effort, and coins were minted from the former pieces. I have long been intrigued by a rumour that a band of cavalier soldiers reputedly salvaged some of the articles and hid them in a safe location. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I have not been able to uncover any concrete evidence for this.

3) Talking of which, I am fascinated by the Peter John Wright painting of Charles II, which is regularly assumed to be a coronation portrait, though it seems more likely to have been painted in 1672

https://www.rct.uk/collection/themes/publications/the-royal-portrait/charles-ii-1630-1685

And Charles is conspicuously showing wearing regal robes, with orb, crown, and sceptre, as if royal authority had been fully restored. Have you any view on this?

It’s a fine painting, isn’t it! I’m no art historian, so I’m happy to follow the experts’ views on this one. Consensus is that it was created sometime 1671-76. It’s entirely possible, of course, some preliminary sketches date from the coronation. I’m afraid I don’t know whether Wright was personally present; the fact that he had not been awarded a royal appointment before 1673 suggests to me it’s unlikely. Intriguingly, your link refers to a mention by Wright regarding the king sitting for him in 1676. Assuming this happened, I wouldn’t be surprised if the work dates from then. As also mentioned, there are clues in the painting that suggest the style is more of the 1670s than 1660s. Charles II also clearly looks older than 31, so I see several reasons to go with consensus regarding the date.

Concerning the second part of your question, there is no doubt that absolute royal authority was not restored following the restoration. Even going back to Magna Carta, absolute monarchy was somewhat curbed. Also, during the reign of Edward II, we see for the first time a separation of the person of the monarch from the institution of the Crown. That said, after Cromwell’s death and the, somewhat ineffective, leadership of his well-meaning son, Richard, large swathes of the country, especially those in senior government, were keen to put an end to the rigid tenure of the protectorate. I think it’s safe to say Charles II’s accession was viewed as a popular one by the country at large, and his later reputation remains a positive one.

4) Have enjoyed your biography on Guy Fawkes, 'Pity for the Guy'. Has to be asked, do you think the Plot had any realistic prospect of success: both as an immediate act of terror, and as leading to a long term Catholic restoration in England and Scotland?

Thanks. Glad that you enjoyed it. It certainly had every chance of working as an immediate action. When questioned in the aftermath, Fawkes even stated bluntly that he would have gladly set light to the lot without means of escape. These were dangerous, desperate men, who worked very hard to create even the slightest opening. Contrary to the beliefs of certain past historians, the volume of gunpowder they had acquired was more than capable of destroying the Palace of Westminster.

Regarding a long term Catholic restoration, I’m not so sure. To achieve this, realistically they would have needed foreign help. The Spanish Treason 1598-1604, of which Fawkes, Thomas Wintour and Kit Wright were a party, focused on obtaining the compliance of the Spanish. The evidence suggests Phillip III wasn’t interested, though that’s not to say he didn’t privately harbour such ambitions. Likewise, I think that the plotters also hoped once news of a successful explosion reached the continent, the Spanish would show their true hand. Difficult to know for sure, as we’re dealing with what-ifs, but I think that might have persuaded them to launch an armada. Whether they would have won the inevitable war or not is another matter. As James I would have been killed, but his impressive son, Prince Henry, and a few others, would have been absent, Henry as de facto heir would likely have had the support of the population at large. On a related note, I’ve always believed it to be such a tragedy he died in his teens, as I think he would have been a brilliant king.

5) Do you think that Robert Cecil and his agents already knew about the Plot far earlier and decided to let it run as it were for various political advantage?

Absolutely – Cecil was a political genius! I don’t believe – as at least two Catholic apologists have conjectured – that the plot was a fabrication, but Cecil had spies everywhere, including the Low Countries. Past investigations into the Monteagle Letter, delivered anonymously to Lord Monteagle on 26 October 1605, some ten days before the intended reopening of parliament, have indicated a clear similarity between the anonymous person’s handwriting and Cecil’s. Also bizarre is Monteagle’s decision to go straight to Cecil, who so happened to be enjoying a late supper with other prominent figures. I think Cecil may have written the Monteagle Letter, albeit after having got wind of the plot from other means.

6) From reading 'Pity for the Guy' and considering how well studied the Plot is, I’m still fascinated by the fact that nobody can work out how the conspirators actually got hold of the gunpowder. What are your thoughts?

If only history’s great conspirators wrote everything down and kept receipts, lol! Very difficulty this one. The government had a monopoly on gunpowder, the majority of which was stored at the Tower. Records from the time show no irregularities, and you didn’t just show up at the Tower to buy gunpowder. Some of the nobility and gentry would have kept a personal stash in their cellars. Yet not even close to the quantities mentioned in the plot – 36 barrels, most likely of firkin size. For me, the most plausible explanation is that they had a contact on the continent. We know from the earlier careers of Fawkes and his accomplices in the Spanish Treason that he had several contacts, not least Sir William Stanley – a colonel in the Spanish army – and renowned spy, Hugh Owen. What I find especially intriguing is that Kit Wright – alias Anthony Dutton in documents concerning the Spanish Treason – was absent from the early plotting. Yet his brother Jack Wright was a founder member. I’ve often wondered if Kit Wright’s missing months concern the purchase and transporting of the gunpowder. Catesby had a small house in Lambeth, to which the powder was initially transported. Taking it over the river to the rented house at Westminster would have been easy enough under cover of darkness, even if it took several trips. Impossible to prove, of course, but in the absence of definitive evidence, I find this most likely.

7) Which other books have you written – both fiction and non-fiction – have a 17th century theme?

8) What are you currently working on?

Further to my latest historical non-fiction, A Hidden History of the Tower of London – England’s Most Notorious Prisoners, published earlier in 2020, Pen&Sword History also commissioned me to write four books on the castle legends and mysteries of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland, as well as my long-time 'work in progress' on the Minority of Henry III and the Marshal War of 1233-34. The Marshall War book was submitted earlier this summer, and I’m also close to finishing the Castles of England book. The complications of Covid-19 et cetera aside, the Marshall War book, and the Castles of England and Wales should all be released between May and November next year, and Scotland and Ireland the first half of 2022. Due to my current non-fiction commitments, The White Hart #4 is presently on hiatus until next year. That book is partially inspired by elements of the Marshal War and will pick up from where The Excalibur Code left off.

Ends.

Comments

Post a Comment